The more one reads, the harder it gets to single out the book to read next. (Is it the same with TV shows and movies?)

Should we read the classics, by local authors or foreign? More works by an author whose previous works we liked? Or should we dip our nose into the contemporary literary scene?

As the best literary works tend to reflect on the primeval mysteries of human nature – something that could fall under the Simone-Weilian use of the word “God” – two novels written a hundred years apart might trail along the very same path, guiding the reader through the same alleyways in cognitive labyrinths.

I never know what to read next I’ve opened a book – either fresh from the bookstore or covered in a thin layer of dust at home – not until I’ve really broken its spine and whiffed the familiar scent of printing chemicals.

My book selection habits could be summarized in a quote by John Cage: “If randomness determines the universe it might as well determine my reading too.”

Books read in 2021

Fave & moving:

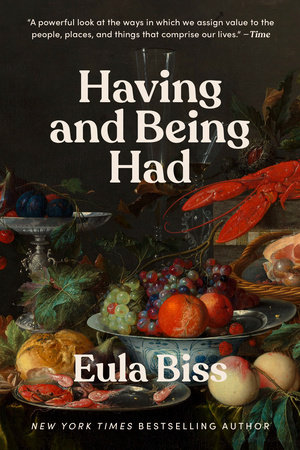

Flights by Olga Tokarczuk | Having and Being Had by Eula Biss | Essays One by Lydia Davis | The Copenhagen Trilogy by Tove Ditlevsen | Saving Agnes by Rachel Cusk | Ada by Vladimir Nabokov | More Die of Heartbreak by Saul Bellow | Stigmata: Escaping Texts by Hélène Cixous | A Mycological Foray by John Cage | Second Place by Rachel Cusk | Index Cards: Selected Essays by Moyra Davey | “Tänapäeva askees” by Hasso Krull | “Imelihtne tulevik : manifeste ja mõtisklusi 1995-2009” by Hasso Krull | Hélène Cixous Reader by Susan Sellers | The Curtain: Essays by Milan Kundera | The Argonauts by Maggie Nelson | Red Doc> by Anne Carson | The Hour of the Star by Clarice Lispector | Unfinished Business: Notes of a Chronic Re-Reader by Vivian Gornick | Play It As It Lays by Joan Didion (re-read) | Speedboat by Renata Adler (re-read) | The Conspiracy of Art: Manifestos, Interviews, Essays by Jean Baudrillard | “Armastus pärast ja teisi lugusid” by Kirjastus Puänt | Strangers to Ourselves by Julia Kristeva | Simone Weil, an Anthology edited by Siân Miles | The Inseparables by Simone de Beauvoir | Simulacra and Simulation by Jean Baudrillard | Exteriors by Annie Ernaux | Checkout 19 by Claire-Louise Bennett | Satantango by László Krasznahorkai | The Moomins and the Great Flood by Tove Jansson | “Oma luulet ja võõrast” by Ilmar Laaban | Drive Your Plow Over the Bones of the Dead by Olga Tokarczuk

Sort of liked:

Arlington Park by Rachel Cusk | Live and Learn: Non-fiction by Joan Didion | On Immunity: An Inoculation by Eula Biss | A Swim in a Pond in the Rain by George Saunders | There Is Simply Too Much to Think about: Collected Nonfiction by Saul Bellow | Se Perdre by Annie Ernaux | Self-Help by Lorrie Moore | Avec mon meilleur souvenir by Françoise Sagan | Laughter in the Dark by Vladimir Nabokov | L’Écriture comme un couteau by Annie Ernaux | “Mitte ainult minu tädi Ellen” by Mudlum | “Vaimu paik” by Jaan Kaplinski | Pitch Dark by Renata Adler | Ways of Re-Thinking Literature edited by Tom Bishop | “Coming to Writing” and Other Essays by Hélène Cixous | L’Evénement by Annie Ernaux | The Originality of the Avant-Garde and Other Modernist Myths by Rosalind E. Krauss

No chemistry:

Weather by Jenny Offill | L’anomalie by Hervé le Tellier | Not a Novel: A Memoir in Pieces by Jenny Erpenbeck | Companions by Christina Hesselholdt | …et toute ma sympathie by Françoise Sagan | The Hatred of Poetry by Ben Lerner | The Actual by Saul Bellow | “Eesti novell 2021” edited by Maarja Kangro | The Irresponsible Magician: Essays and Fictions by Rebekah Rutkoff | On Freedom: Four Songs of Care and Constraint by Maggie Nelson | Screen Tests by Kate Zambreno | Memento Mori by Muriel Spark | The Last Supper: A Summer in Italy by Rachel Cusk | Illuminations: Essays and Reflections by Walter Benjamin | “Armastus” by Loone Ots

2021 Fave short fiction & longform essays

A haphazard list of short stories, interviews, and essays, collected over the year and rummaged while revising my reading notes.

Short stories:

- Yente by Olga Tokarczuk via The New Yorker, link

“Kuumalaine” by Asta Põldmäe

Lady Neptune by Ann Beattie via Granta, link - The Winged Thing by Patricia Lockwood via The New Yorker, link

- How to Be an Other Woman by Lorrie Moore, link

- The Saint by Gabriel García Márquez via The Paris Review, link

- The Lives of Saints by Jeanette Winterson via The Paris Review,, link

- The Beach Boy by Ottessa Moshfegh via The New Yorker, link

Essays & reportage:

- An Island of One’s Own by Emanuele Coccia via Purple Magazine, link

- Splash, Marina Warner via The New York Review of Books, link

- Phantasms of the Opera by Larry Wolff via The New York Review of Books, link

- Spirited Away by Anne Enright for The New York Review of Books, link

- The Resistance by Eula Biss via The Paris Review, link

- How to Rescue Literature by Roger Shattuck via The New York Review of Books, link

- Uhtceare by John Jeremiah Sullivan via The Paris Review, link

- Confidence Man by Roger Shattuck via The New York Review of Books, link

- A Mind in Pain by Gregory Hays via The New York Review of Books, link

- Napoleon’s Greatest Trophy by Jenny Uglow via The New York Review of Books, link

- The Sixth Taste by Daniel Soar via the London Review of Books, link

- Murder Is My Business by Caroline Fraser via The New York Review of Books, link

- Know Thyself by Meghan O’Gieblyn via The Paris Review, link

- Russian Metamorphoses by Rachel Polonsky via The New York Review of Books, link

- Women Artists and the Looking Glass by Jennifer Higgie via Frieze, link

- Picture Books as Doors to Other Worlds by Elissa Washuta via The Paris Review, link

- The Landlord’s Game: the Anticapitalist Origins of Monopoly by Eula Biss via LitHub, link

- Shifting Baselines by Callum Roberts via Granta, link

- Water Is Never Lonely by Judith D. Schwartz via Granta, link

- Vultures by Samanth Subramanian, Granta, link

Thoughts + passages from the books read and very much recommended:

Compared to the previous year, my reading preferences became ever more skewed towards indie presses and French authors. The luckiest discovery was the Polish writer Olga Tokarczuk whose humanist novels melange history, mystery, and philosophical reflections. Drive Your Plow Over the Bones of the Dead was the best novel I read this year (and my go-to Christmas gift this season).

I discovered and read a lot of Hélène Cixous‘ essays verging on the liminal space between poetry and philosophy. Through Cixous, I came upon Clarice Lispector – a Brazilian novelist cherished by the former, famous for her poetic yet unforgivingly cruel stories, written as in a flow of stream-of-consciousness. The new book by Claire-Louise Bennett, Checkout 19, was another favorite, as were Lydia Davis’ essays on writing and translation.

While vacationing in Estonia this summer, I broke the spell of not having read any Estonian authors since high school and spent hours after hours soaking in the sun while reading Hasso Krull‘s “Tänapäeva askees” + his essays on dark ecology. I also came upon the writing by Asta Põldmäe, Ilmar Laaban, Ave Taavet, Viivi Luik, Mudlum, Loone Ots, and many other (mostly contemporary) Estonian writers. The verdict? To read more homeland literature (as well as translations of other authors exterior to the Anglo-American literary canon).

More essayists – Eula Biss, Maggie Nelson, Moyra Davey – landed on my bookshelves. Of familiar writers, Anne Carson, Rachel Cusk, Joan Didion, Vladimir Nabokov, Renata Adler, and Annie Ernaux kept reappearing in the reading menu. Rachel Cusk‘s new novel Second Place, exploring the existential crisis in our modern times, was a new favorite.

Two autobiographical novels – The Copenhagen Trilogy by Danish writer Tove Ditlevsen + the first-time publication of Simone de Beauvoir’s coming-of-age memoir The Inseparables – were a comforting read.

The long November evenings were accompanied by pertinently dark and saturnine novel Satantango by the Hungarian writer László Krasznahorkai + grim yet hopeful Moomin stories by the Finnish writer Tove Jansson.

Below are some recommendations of my fave books read in 2021.

Drive Your Plow Over the Bones of the Dead by Olga Tokarczuk

This novel by the Polish writer Olga Tokarczuk immediately became an all-time favorite: the perfectly balanced stitchwork weaving together a crime story and philosophical abstractions, deeply shaking episodes arousing anger and joy, the ornate use of language that survived translation from Polish to English.

The story follows Janina, a former engineer turned English teacher, now living in a solemn Polish village amidst mountains and forests. Things take an eerie turn when one winter night her neighbor dies, choking on the bone of a deer he’d hunted and eaten the very same day. Other mysterious deaths follow and animals seem to play an increasingly apparent role of the revenant. As the plot thickens, the novel ventures into philosophical (and at times darkly comical feminist) musings on love, aging, religion, human-animal relationship, and citizen activism pushed into extremes.

Some highlights from the book:

“It’s hard work talking to some people, most often males. I have a Theory about it. With age, many men come down with testosterone autism, the symptoms of which are a gradual decline in social intelligence and capacity for interpersonal communication, as well as a reduced ability to formulate thoughts. The Person beset by this Ailment becomes taciturn and appears to be lost in contemplation. He develops an interest in various Tools and machinery, and he’d drawn to the Second World War and the biographies of famous people, mainly politicians and villains. His capacity to read novels almost entirely vanishes; testosterone autism disturbs the character’s psychological understanding.”

“I grew up in a beautiful era, now sadly in the past. In it there was great readiness for change, and a talent for creating revolutionary visions. Nowadays no one still has the courage to think up anything new… Reality has grown old and gone senile; after all, it is definitely subject to the same laws as every living organism – it ages. Just like the cells of the body, its tiniest components – the senses, succumb to apoptosis. Apoptosis is natural death, brought about by tiredness and exhaustion of matter. In Greek this word means ‘the dropping of petals.’ The world has dropped its petals.”

“I noticed a pregnant girl sitting on a bench, reading a newspaper, and suddenly it occurred to me what a blessing it is to be ignorant. How could one possibly know all this and not miscarry?”

Exteriors by Annie Ernaux

In the 1990s, the French writer Annie Ernaux traveled the RER train between a Paris suburb and the city, observing people in transit and in shopping malls. In Exteriors, she recollects some of her daily encounters and impressions, at times interrupting the narrative to question what is the point of her doing all this. The fragmented form allows Ernaux to present clear-cut momenta liberated of weighty contextual implications that placing her characters in a novel would proclaim.

Rousseau’s quote in the prolong – “Our real self is not entirely inside of us” – invites the reader to get immersed in the humming quotidian rhythm of the city life, becoming one with the flow of masses. This brings to mind Walter Benjamin’s reflections (in essay collection Illuminations) on the character of flaneur, skimming the streets of Paris and cherishing the anonymity of moving amid the kinetic mass of strangers.

In a society of dull repetition and sameness, Ernaux’s diaristic essay-novel is a memento vivere that reminds us to search for meaning and guidance in the small details around us. Taking a train or walking in a mall, we become part of the exterior experienced by other people, while through the intricate entwining of our lives with those of strangers, our interiors get shaped and altered, deconstructed and reanimated.

“So it is outside my own life that my past existence lies: in passengers commuting on the Metro of the RER; in shoppers glimpsed on escalators at Auchan or in the Galleries LaFayette; in complete strangers who cannot know that they possess part of my story; in faces and bodies which I shall never see again. In the same way, I myself, anonymous among the bustling crowds on streets and in department stores, must secretly play a role in the lives of others.”

Second Place by Rachel Cusk

Rachel Cusk’s 11th novel (and my favorite at that) Second Place owes its inspiration to Mabel Dodge Luhan’s 1932 memoir Lorenzo in Taos, depicting D.H. Lawrence’s stay at her artists’ retreat in New Mexico. The reference, revealed as late as in endnotes, provides Cusk with an alibi of sorts.

After receiving excruciatingly judgemental feedback to her autobiographical books A Life’s Work and Aftermath, the author has chosen to shelter behind 3rd-person narrators: in her much-celebrated Outline trilogy, the narrator Faye tells us stories heard by others met on her journey.

In Second Place, Cusk is relying on her protagonist M (Mabel) to recount the tale to an unknown confidante Jeffers (Robinson Jeffers was a poet and a guest to Luhans’ New Mexican estate). And while L, the name for the artist visiting M, stands for D.H. Lawrence, the philosophical questing towards existential salvation – the overarching subject of this book – is unmistakably Cusk’s own.

I wrote a longform review of the book here, so I won’t stop on it for long. Below are some of my favorite lines from the novel.

“Life rarely offers sufficient time or opportunity to be free in more than one way.”

“The truth was I had always believed that pleasure was something I was amassing in a bank account, but by the time I came to ask for it I discovered the store was empty. It appeared that it was a perishable entity, and that I should have taken it a little earlier.”

“I’ve often thought it’s fathers who make painters,” he said, “while writers come from their mothers.” I asked him why he thought that. “Mothers are such liars,” he said. “Language is all they have. They fill you up with language if you let them.”

“The truth lies not in the claim of reality, but in the place that where what is real moves beyond our interpretation of it. True art means seeking to capture the unreal. Do you think so, Jeffers?”

The Copenhagen Trilogy by Tove Ditlevsen

It rarely happens that a Scandinavian author’s works, revered in her motherland yet completely neglected in the Anglo-American literary world, gets translated to English posthumously.

Tove Ditlevsen was born in 1917 in a working-class neighborhood in Copenhagen. Through a succession of lucky encounters and chances taken (or often, being thrown into), she become one of the best-known Danish writers. Ditlevsen’s memoir begins in her childhood home where she shadows her disturbed and desolate mother, then moves on to the young adult’s wrestle into the local literary society. Just as Ditlevsen has achieved her hard-won literary celebrity and financial independence, a new dependence looms over her life, annexing her body and mind in addiction for Demerol and methadone, and draining her esprit of life.

The story is moving as much as the open confessions of Ditlevsen’s disloyalty to the people in her life and her all-encompassing ambition and self-absorption are repelling. While the memoir ends on a hopeful note – Tove has found a man that she loves and that loves her back just as much, she is through with her rehabilitation and learning to keep her addiction at bay – the knowledge that she ended her life with a suicide twenty-something years later impends like a dark cloud after finishing the book.

At times, reading the book, I found myself wondering if the occasionally flat prose and prosaic scenes were amplified by its English translation. Then another Scandinavian writer surfaced in my mind, also named Tove (Jansson), whose memoirs published in a series of works – The Sculptor’s Daughter, The Summer Book and The Winter Book – are written in analogous clean-cut ice-cold prose at times fantastical but not. Ditlevsen and Jansson both drew material from their own life, laid it out for the potential vultures for each to take their cut, and emerged as beloved authors, characters between tangible and fictional.

Ada, or Ardor by Vladimir Nabokov

Published two weeks after his seventieth birthday, Ada, or Ardor is one of Nabokov’s masterpieces and a culmination of his career as a novelist. The book tells a love story troubled by incest. But more: it is also at once a fairy tale, an exercise in utopia, a philosophical treatise on the nature of time, a parody of the history of the novel, and an erotic catalog. While the overlying story of two siblings taking romantic interest in each other is intriguing in its own right, the beauty of Ada first and foremost lies in Nabokov’s virtuosic use of language – English, French, and Russian – all intertwined in a panoramic nostalgia for intellectualism.

Some favorite quotes and notes from the book:

“I am sentimental,’ she said. ‘I could dissect a koala but not its baby. I like the words damozel, eglantine, elegant. I love when you kiss my elongated white hand.”

“Hammock and honey: eighty years later he could still recall with the young pang of the original joy his falling in love with Ada. Memory met imagination halfway in the hammock of his boyhood dawns. At ninety-four he liked retracting that first amorous summer not as a dream he had just had but as a recapitulation of consciousness to sustain him in the small gray hours between shallow sleep and the first pill of the day. Take over, dear, for a little while. Pill, pillow, billow, billions. Go on from here, Ada, please.

(She). Billions of boys. Take one fairly decent decade. A billion of Bills, good, gifted, tender and passionate, not only spiritually but physically well-meaning Billions, have bared the jillions of their no less tender and brilliant Jills during that decade, at stations and under conditions that have to be controlled and specified by the worker, lest the entire report be choked up by the weeds of statistics and waist-high generalizations.”

[Ada playing anagrams with Grace, who had innocently suggested ‘insect.’]

‘Scient,’ said Ada, writing it down.

Oh no!’ objected Grace.

‘Oh yes! I’m sure it exists. He is a great scient. Dr Entsic was scient of insects.’

Grace meditated, tapping her puckered brow with the eraser end of the pencil, and came up with:

‘Nicest!’

‘Incest.’ said Ada instantly.

‘I give up,’ said Grace. ‘We need a dictionary to check your little inventions.’

Hour of the Star by Clarice Lispector

Brazilian writer Clarice Lispector’s style – inexhaustible stream-of-consciousness romance – feels like a drop of iris-scented oil in an unforgivingly salty ocean. Reading her novels is akin to reading poetry which means that I often struggle with attuning to Lispector’s writing.

Yet there’s always a story, always an abundance of original ideas. Hour of the Star is a novella that Lispector wrote in old age, pouring a poor girl’s life story into a glimmering stream of off-kilter details and ironic sadness.

Some lines from the book:

“All the world began with a yes. One molecule said yes to another molecule and life was born. But before prehistory there was the prehistory of prehistory and there was the never and there was the yes. It was ever so. I don’t know why, but I do know that the universe never began.”

“Most of the time she had without realizing it the void that fills the souls of the saints. Was she a saint? So it seems. She didn’t know that she was meditating because she didn’t know what the word meant. But it seems to me that her life was a long meditation on the nothing. Except she needed others in order to believe in herself, otherwise she’d get lost in the successive and round emptiness inside her. She meditated while she was typing and that’s why she made even more mistakes.”

“There was one ad, the most precious of all, that showed in full color the open pot of cream for the skin of women who simply were not her. Blinking furiously (a fatal tic she had recently acquired), she just lay there imagining with delight: the cream was so appetizing that if she had the money to buy it she wouldn’t be a fool. To hell with her skin, she’d eat it, that’s right, in large spoonfuls straight from the jar. Because she lacked fat and her body was drier than a half-empty sack of crumbled toast She’d become with time mere living matter in its primary form.”

The last paragraph, apart from the rest on the tale:

“And now – now all I can do is light a cigarette and go home. My God, I just remembered that we all die. But – but me too?!

Don’t forget that for now it’s strawberry season.

Yes.”

Red Doc> by Anne Carson

Anne Carson’s writing never yields to any set-in-stone literary category. Her intellectual and poetic verse-novels alluding to Greek myths, Simone Weil’s philosophy, and other poets’ work are free-flowing, playfully grammatically incorrect, and full of morbid humor.

Red Doc> follows the characters of Autobiography of Red, a modern re-telling of a Greek myth, the 10th labor of Herakles — killing the red-winged monster Geryon. The protagonists reunite in Red Doc> middle-aged. Geryon is now G, still a cattle-herder, Herakles is now called Sad But Great — “Sad for short.” On the other hand, reading the book without a clue of its origin story, one can enjoy it as a poetic journey in the company of lunatics and a sheep named Io.

“… Between any

two activities he plunges.

Can’t stand to be alone

hates quiet time has little

interest in introspection let

alone other people as

individuals. Or rather he

doesn’t care for people he

cares what flows through

them. And usually takes

it. His teacher at med

School called him a

minotaur who swallows

other people’s labyrinths.

Good I’ll do psychiatry he

said.

Plowing can be

Brutal. So too hauling, Io

prefers ambling. Ahead of

the herd at her usual pace in

her usual leadership role on

their usual way to summer

pasture. Not summer yet

but here they go. That’s not

usual. M’hek walks slightly

behind her. He’s not usual.

The wind is from the north.

Usual. Her head itches.

Usual. She stops and

Lowers her head to scrape

one horn against a patch of

gorse. The gorse smells

interesting. She bites off

some and stands a while

working it against her

mostly toothless upper jaw.

Especially pungent this

gorse. Is is half-fermented

and will cause her mild

hallucinations all the rest of

the day. Or perhaps not so

mild.”

Mushroom Book by John Cage, Lois Long, Alexander H. Smith

John Cage: A Mycological Foray offers an aesthetic trip into the mycophile mind of avant-garde composer John Cage. Volume I includes an essay on Cage’s lifelong passion for mushrooming and the full transcript of Cage’s 1983 1.5-hour performance Mushrooms et Variationes. Volume II, certainly one of the most beautiful printed works I’ve ever encountered, holds a reproduction of Mushroom Book, a collaborative project between Cage, writer and illustrator Lois Long, and botanist Alexander H. Smith.

Leafing through the mushroom book made me fall into a pleasant obliviousness, purposeless and yet important. As Cage noted: “I don’t have any favorite mushrooms – I just like the one I have. I love mushrooms, that’s all. When you love something you don’t ask what draws you to it. You remember that you decided to love it, and the rest is just life experience.” One can’t really argue that, can we?

Also wrote a longer review with some quoted mesostics here: John Cage: A Mycological Foray

Stigmata by Hélène Cixous

There is no writer I know of who’d write in English like Hélène Cixous writes in French, and her unique and romantic sensibility towards language – words, puns, double entendres, quotes, poems, and metaphors that collide in her patchwork essays – should leave no language nerd indifferent.

After finding Stigmata, I read an ample selection of her other writing, but this first encounter remained the most touching. No less for the admirable work by the translator who left the text dappled with references and explanations of the original French version.

Some quotes from the essays:

“I advance error by error, with erring steps, by the force of error. It’s suffering, but it’s joy.

I seek the truth, I encounter error. How do I recognize error? It is obvious, like truth. Who tells me? My body. Truth gives us pleasure. It makes us burst out laughing, trembling. Blushing. It’s hot. It’s like this: I grope. I try the word ‘hesitation.’ I taste it. No pleasure. No taste. I cross it out. I try: ‘correction.’ I taste. No. I taste ten words. Finally I fall for the word ‘essay.’ Before even trying I sense a pretaste… I taste. And, that’s it! Its taste is strong and fine and rich in memories of pleasure.”

“For us, eating and being eaten belong to the terrible secret of love. We love only the person we can eat. The person we hate we ‘can’t swallow.’ That one makes us vomit. Even our friends are inedible.”

“Loving is wanting and being able to eat up and yet to stop at the boundary. And there, at the tiniest beat between springing and stopping, in rushes fear.”

“Now the wolf can no longer break away from the lamb, for the lamb retains, for better or worse, traces of the gift. That which is given in love can never be taken back. It is me my entire self that I give with the gift of love. This is why the wolf can’t stop loving the lamb, the chosen one. Repository of the wolf. All of the wolf. That’s how love can ruin the lover.”

“Millions of signs rain down and in their flood they stick to one another, they kiss.”

Having and Being Had by Eula Biss

Eula Biss has a talent for weaving research and poetic essayism with prosaic perceptions from her own day-to-day existence. She also likes to place high bets on her chosen subjects. The subject of her previous book On Immunity – vaccinations – was a daring and dividing choice. As if to keep her adrenaline inflow steadily pumped, Biss has chosen capitalism as the epicenter of her latest book. Having and Being Had is a poetics of consumerism (or is it rather a blues?), and Biss turns capitalism into a fluid metaphor to be sprayed on any modern phenomena lacking a readily coherent explanation.

To unweave the intricate systems of capitalism that she’s a participating member of, Biss combines her personal perceptions with a consultation into the works of economists and anthropologists, thinkers and writers from ancient Greece through to 21st century. The result is a book of 5-page-long essays exploring the various countenances of life in the modern (that is, capitalist) society.

“Do you think it’s wrong,” a taxi driver asks Eula Biss on a ride home, “to make money teaching

something that won’t earn your students a living?” Biss, who teaches creative writing at Northwestern University, answers with a “no.” According to her ethics, the service she is doing for her students is teaching them how to find value in something that isn’t widely valued. “And I think it’s a gift to give another person permission to do something worthless.” In the end of the ride, she asks the driver what he thinks of her views and he replies “I think it’s wrong.”

The book is filled with similar stories of Biss’ life as a member of the consumer society, fragments that leave her confused and induce bittersweet guilt. On a visit to a friend’s apartment with “a new IKEA desk in the living room, which is also the office and the dining room,” her friend asks: “Is this what we do now? We just keep earning money and replacing this stuff with better stuff?”

One of the pitfalls that also lends the book its credibility is the fact that Biss herself is far from asymptomatic to the allures of capitalism. She has recently bought herself a new house (she tells others that it cost $400,000, embarrassed to have paid $500,000) and accepted a $40,000 advance to buy herself time to write this book. “The spies are artists, I think, or anyone who lives inside a value system that is not their own,” Biss comments. “I want to be a class traitor, but I suspect that I’m more attracted to the romance of treason than reality.”

Index Cards by Moyra Davey

Moyra Davey’s essay collection ranges between photography, writing, and visual arts. Each essay is a permission and a purpose for Davey to delve into the works of her favorite authors – including Franz Kafka, Susan Sontag, Walter Benjamin, Simone Weil, Italo Calvino, John Cage + many others) and to craft their thoughts, quotes, and her own ideas into a free-flowing meditation on the subject.

The way Davey describes her multifarious reading habits is highly relatable.

“Reading is a favorite activity, and I often ponder its phenomenology. … Sometimes it feels like a literal ingestion, a bulimic gobbling up of words as though they were fast food. At other times I read and take notes in a desultory, halting, profoundly unsatisfying way. And my eyes hurt.”

As such essay collections go, it left me with a long list of books to read next.